Reinventing a Dual Language Program

The ACIE Newsletter, February 2008, Vol. 11, No. 2

By Ana María Chacón, Third Grade Teacher, Barbieri Elementary School, and Sara Hamerla, Assistant Director of the Bilingual, ESL and Sheltered English Programs, Framingham Public Schools, Framingham, MA

| “Yo me sentí orgullosa, feliz, y contenta y mi mamá se sintió igual pero yo creo que ella se sintió el triple que yo me sentí.” | “I felt proud, happy, and content and my mother felt the same, but I believe that she felt triple as much as I felt.” |

Jennifer, in her essay entitled, “Proud to be Bilingual,” described her pride at her ability to translate a letter from English to Spanish for her mother. Jennifer is a fifth grade student in the Two-Way Dual Language Program at Barbieri Elementary School.

Second grade children from the Barbieri Two Way Program during a language arts class

Since its inception, the program has aimed to promote bilingualism and multiculturalism. But just as language acquisition takes time, the development of the ideal program has also been a lengthy, albeit worthwhile, process.

Two-Way Design

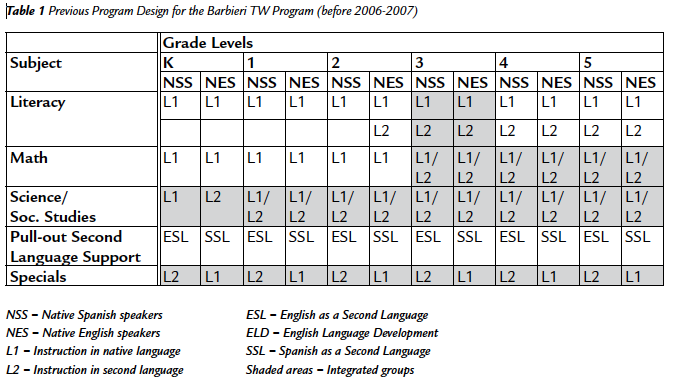

In the late 1980s, a group of Barbieri School teachers, parents, and the principal sought to unite a school divided into standard curriculum classrooms and bilingual classrooms. Over several years, a committee at the school planned the implementation of a Spanish-English dual language program. In 1990, the Two-Way Program began in kindergarten and first grade with support from Title VII federal grant monies. Each year, another grade was added. The program now extends from kindergarten through twelfth grade. Of the approximately 600 students in grades K-5 at Barbieri School, 412 (69%) are enrolled in the Two-Way Program. A two-way immersion program aims to enroll equal numbers of native English speakers and native Spanish speakers. One of the advantages of this dual target population is that native speakers of each language can serve as models for language learning (Freeman, Freeman & Mercuri, 2005). As students learn together, they develop positive attitudes toward their own language and culture and the second language and culture. Under the Barbieri two-way model, as it was originally designed (see Table 1),

students received initial literacy instruction in their native language. In the early grades, students moved between two teachers during the school day. During the morning, they were separated by native language for literacy and math; in the afternoon they were integrated for social studies and science (integrated times are indicated by shaded areas). By the upper grades, integrated groups of students were expected to be able to have developed enough biliteracy to be able to spend one week with a Spanish-speaking teacher and the next week in English. In this model, academic time in integrated groups was very limited in the early grades in order to preserve a high quality of native language instruction, especially for native Spanish speakers (de Jong, 2002). When teachers instructed in integrated groups, it was believed that instructional adaptations, made for native English speakers, would oversimplify the language, in essence, watering it down. Over time, however, it became apparent that the program model was postponing the need to prepare students to understand higher levels of academic Spanish. When students reached the upper grades, and the model required students to spend each week integrated and immersed, teachers were struggling to incorporate higher order thinking, address the content areas and build vocabulary.

Climate for ChangeOver the past fifteen years, the Two-Way Program has been recognized as a site of excellence. In 2001, the school was included in the Portraits of Success project. This project identified and published the characteristics and outcomes of successful bilingual education programs (www.alliance.brown.edu/pubs/pos). Under the leadership of the current principal, Minerva González, a former second grade teacher in the Two-Way Program, the Barbieri School has received accolades. Barbieri was designated a 2004 Compass School by the Massachusetts Department of Education for exemplary programs and practices leading to improved student performance. Yet the Barbieri staff saw the need for improvement. At the fifteen-year anniversary of the program, teachers and administrators took the next step professionally and revisited the progress towards the goals of the program. This reform effort was the result of a consensus among teachers of the upper grades that students in the program would benefit from reaching higher academic and linguistic levels of Spanish earlier on. In addition, parents of kindergarten and first grade native English-speaking children expressed a desire for more instructional time in Spanish.

Implementing Thoughtful Reform

It was time for change. Empowered by the feedback from teachers and parents, the program’s self-study was launched by the district’s Director of Bilingual, ESL, and Sheltered English Programs, Susan McGilvray-Rivet, during summer 2005. Funds from Title III supported a three-day workshop for twenty Two-Way Program teachers that focused on an evaluation of the entire K-5 program. The Guiding Principles for Dual Language Education (Howard et al., 2005) was employed during the workshop as a roadmap and tool for planning, self-reflection, and growth. The Guiding Principles are organized into seven strands (assessment and accountability, curriculum, instruction, staff quality and professional development, program structure, family and community, support and resources) representing the major areas of program implementation. Teachers rated the Barbieri Two-Way Program on a scale from minimal to exemplary in these seven areas. After much discussion, four areas were prioritized for change: support and resources, curriculum, instruction, and program structure. As the 05-06 school year began, teachers shared their summer work with the rest of the Two-Way Program staff. Then, each teacher joined a committee that began meeting regularly to develop action plans for change in each of the four areas identified.

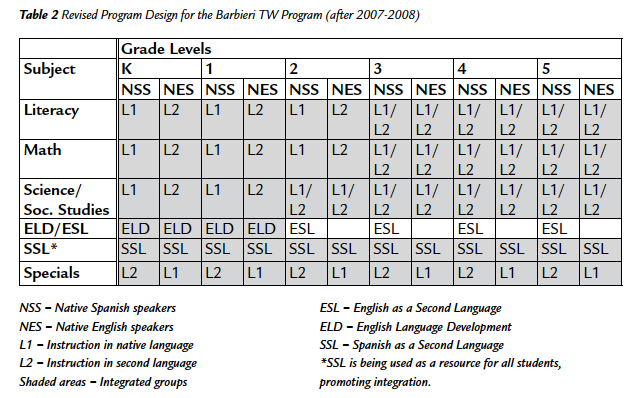

Teachers Call for Progressive Curricular Revisions

A group of fifteen teachers organized into the Curriculum Committee and periodically met on Saturdays and after school. The task of this group was to determine the progress towards the goal of biliteracy and bilingualism for all students. The district’s program director, along with an outside consultant, guided the committee. First, teachers began a thorough review of recent research on dual language programs. Informed by the research, teachers suggested changes in the program design. They identified a need to increase the amount of Spanish instruction for native English speakers in the early grades. More Spanish instruction in grades K-2 would allow for a smoother transition to the upper grades when students are immersed in Spanish biweekly. In addition, the native Spanish speakers would benefit because the native English speakers would have more sophisticated language skills needed to engage in high-level academic instruction. In the original model, native Spanish speakers were not always challenged to their potential during integrated instruction time in Spanish because the teacher had to make significant accommodations for the lower second language proficiency levels of the native English speakers (Lindholm-Leary, 2001). The committee also used assessment results based on tests given in English to determine past progress toward program goals. Research analyzing test data from Two-Way Program cohorts indicates that both native English-speaking and native Spanish-speaking students outperformed Hispanic students and English language learners in the state in most areas (de Jong, 2002, 2006). Results of the Massachusetts English Proficiency Assessment (MEPA) revealed that native Spanish speakers in the program make great gains in English acquisition. While data from standardized assessments was encouraging, it was time to raise the bar and ensure that all students were achieving at high levels in both languages. The Curriculum Committee shared their work with the rest of the Two-Way Program staff. All teachers understood that the amount of instruction for native English speakers in Spanish needed to increase. All agreed, however, that major changes could not happen de la noche a la mañana (immediately). It was clear from the research that the ideal program design for the Two-Way Program population was an 80/20 model. In this model, students in kindergarten and first grade should receive 80% of instruction in Spanish and 20% in English. In grade 2, all students should receive 70% of instruction in Spanish and 30% in English. Instruction should remain 50% in English and 50% in Spanish in grades 3, 4, and 5, as in the present design. In these upper grades, students spend alternating weeks in Spanish with a Spanish-side teacher and in English with an English-side teacher. This model will prepare students to meet the challenges of learning and academic achievement in both languages. This new model is being phased in over several years (see Table 2).

In 06-07, kindergarten and grade 1 and 2 teachers began to instruct more content area units in Spanish. Spanish literacy instruction for all kindergarten students started this year, 07-08, and will be phased in for students in grades 1 and 2 during subsequent years. This will allow for more instruction of integrated groups of native English- and native Spanish-speaking children, increasing opportunities for social interaction.

How Strong Leadership Initiates ChangeThe decision made by the program director and the school principal to involve teachers in the reform process was the major factor contributing to its success. The two administrators recognized the collaborative culture of the Two-Way Program teachers and valued their expertise. As the process of change moves forward, the principal and program director will jointly assume responsibility for guiding and supporting teachers and families. When channels of communication are open and goals are clear, members of the school community are willing to invest time and energy in education. At the Barbieri School parents and teachers are united in their pursuit of positive changes that will ultimately result in student learning. Effective leadership is needed among teachers and parents as they continue the work of the committees. One teacher involved in the reform effort noted, “Although change can be uncomfortable and cause anxiety, teachers and parents are willing to dedicate themselves when we see change lead to improved student learning.” The Barbieri School is fortunate to have teachers and parents engaged in “two-way” communication, improving education for our bilingual children.

References

Cloud, N., Genesee, F., & Hamayan, E. (2000). Dual language instruction: A handbook for enriched education. Boston, MA: Heinle and Heinle.

Christian, D., Genesee, F. Howard, L. & Lindholm-Leary, K. (November, 2004). Project 1.2 Two-way immersion. Final Progress Report. Available from www.cal.org/twi/CREDEfinal.doc.

de Jong, Ester. (February, 2006).Two-way immersion. Paper presented at the annual conference of NABE, San Antonio, TX.

de Jong, Ester. (2002). Effective bilingual education: From theory to academic achievement in a two-way bilingual program. Bilingual research journal 26 (1): 1-15.

Freeman, Y., Freeman, D. & Mercuri, S. (2005). Dual language essentials for teachers and administrators. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Howard, E., Sugarman, J., Christian, D., Lindholm-Leary, K., & Rogers, D. (2005). Guiding principles for dual language education. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. Available from www.cal.org/twi/guidingprinciples.htm.

Lindholm-Leary, K.J. (2001). Dual language education. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.